Open Thread Thursday

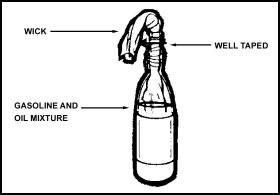

The Finnish Army developed the "Molotov Cocktail" to defend against Soviet tanks in World War II, according to Wikipedia.

The Finnish Army developed the "Molotov Cocktail" to defend against Soviet tanks in World War II, according to Wikipedia.On Wednesday, a little old lady in Bel-Air found one on her doorstep -- a Molotov Cocktail, not a Soviet tank.

How did it get there? Terrorist malpractice.

The septugenarian woman, it turns out, is a neighbor of a woman named Lynn Fairbanks. So reports NBC Channel 4. Fairbanks was the intended target, not the little old lady neighbor.

CBS Channel 2 says the "Animal Liberation Front" admitted leaving the firebomb: "According to the ALF, Fairbanks is notorious at UCLA for keeping hundreds of vervet monkeys in cages to study psychological, psychiatric and social problems such as Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD), substance abuse, criminality and violence."

Now, your first thought is probably, "What the hell is 'vervet'? Is it like 'velvet'?"

But the better question is, do they seriously think this is going to help their cause? Or maybe their "cause" isn't really to help animals at all, but instead to experience the "high" of living as "freedom fighters." Yikes.

Anyway, the FBI is offering a $10,000 reward.

In an unrelated story, the USA Network showed "Twelve Monkeys" Wednesday night; the History Channel featured a show on the history of taxidermy. Also "yikes."

33 Comments:

At least a Molotov cocktail team, 2 guys with cocktails and 2 guys with logs to jam the tank treads - allowing the cocktails to burn better on a stalled tank. Finnish cocktail teams took 78% casulties during the war.

HeadOn, apply directly to the forehead!

HeadOn, apply directly to the forehead!

HeadOn, apply directly to the forehead!

HeadOn is available without a prescription at retailers nationwide.

Always look to Mayor Sam for the facts.

Anybody remember the Russian Revolution?

I believe (know) that Molotov, a real person, was there and invented that cocktail around 1917 to throw at the Czar's forces.

The ALF deserves whatever it gets in the wake of incidents like this. They mistake their self-righteousness for rationality and, like any "good" terrorists, put innocent people at risk along with their intended targets.

That isn't to say that their targets deserve this violence either, but it's hard to support a crusade on behalf of innocent animals when its purveyors are willing to kill innocent humans for their cause.

With home prices so high I wish it was Russia.

9:36,

The molotov cocktail was named after Vyacheslav Molotov, but he didn't invent it or name it himself. Some Finns named it after him since he was largely to blame for Russia's invasion of Finland in 1939.

JOSE HUIZAR FOR SALE:

Minutes before they took up the issue of campaign finance, the council approved a controversial home-construction project in Mount Washington, a neighborhood represented by Councilman JOSE HUIZAR. Nothing on the Ethics Commission Web site — the repository for campaign-finance data — told Huizar’s constituents that their councilman had a $500-per-ticket fund-raiser in February at the Century City law offices of Ben Reznik, the attorney representing the home developer. Nothing in the public record said the event was billed as an informal discussion of housing and development, or that a leading opponent of the project — Daniel Wright, president of the Mount Washington Homeowners Alliance — co-hosted his own Huizar fund-raiser weeks later.

8:19 AM

Um, OK. So why is this home construction project controversial? If an elected official receives a donation from an attorney, does that mean that the elected can never vote on any issue that involves the attorney's clients?

I hear what you're saying, but show us the exact proof that Weezie is selling out.

VOTE NO ON THE $1 BILLION "AFFORDABLE-HOUSING" (SHAM) BOND MEASURE proposed for the November ballot.

This bond measure would cost city property owners an average of $14.66 annually on each $100,000 of assessed property value for 20 years.

Trash fee hikes, LAUSD bonds, lavish city council compensation, mayor's employees 10% one year pay increase, etc. etc. ENOUGH IS ENOUGH!

VOTE NO!!

Notice that the CBS story called ALF an "activist" group. At least UCLA got it right by calling them a "terrorist" group. Why does the media so often mince words?

Dear 8:55 am. Mincing the words is a courteous phrase -- unlike most on blogs, courteous that is. The media is PC!

PC rules today. Not honesty.

CD14 Office=ALF

Joe Ramallo: Doing AV's dirty work again? Leave LAPD alone and get a life dude!

Remember Florida Scandal?

Do you want us to go there?

Office of the Mayor

City of Los Angeles

ANTONIO R. VILLARAIGOSA

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Joe Ramallo

July 12, 2006 (213) 978-0741

MAYOR VILLARAIGOSA’S STATEMENT ON THERA BRADSHAW’S

RESIGNATION AS THE GENERAL MANAGER OF THE INFORMATION

TECHNOLOGY AGENCY

“As the General Manager of the City of Los Angeles Information Technology

Agency (ITA) for the past two years, Thera Bradshaw has worked tirelessly to

advance technology’s role in our city and government.

During her tenure, ITA has furthered its efforts to offer wireless service Internet

access to visitors and link citizens to downtown city council meetings via live

video teleconferencing technology, among other initiatives.

The need to improve technological services and opportunities to our residents is

as great as any need facing the City of Los Angeles and Ms. Bradshaw met this

challenge with enthusiasm.

I wish Ms. Bradshaw much success and enjoyment in her retirement and I

congratulate her on a job well done.

Ms. Bradshaw’s years of service have been invaluable to the City of Los Angeles

and her commitment to government technology is admirable.

I look forward to naming an interim General Manager in the coming weeks as we

embark on a national search to find the most qualified candidate to lead the

Information Technology Agency in the years to come.”

###

Huizar is selling out because he's selling his vote to the highest bidder. Dozens of people that have homes surrounding this property were against it. Instead, Jose sided with the law firm that hosted the fundraiser.

I guess that should not surprise me. Jose was for sale on the school board and, my guess is, that his price has only increased since he's been on the Council.

Sleazy Weezie is a moron. Too bad those law degrees aren't helping him as councilman. He's getting slammed at community meetings and now is considered Antonio's puppy and gofer. He lost his crediability a long time ago and people now just laugh at him. He's not taken seriously and sadly has become as slimy as Antonio. Interesting no one ever thought of Weezie like that until he aligned himself with AV. AV on the other hand on tv today talking about potholes. Someone should hire one of those guys who goes to events and throws a pie in the face of people for $50. That would be funny.

3:01 PM,

I don't live in CD14. Does it look like Huizar will lose his re-election campaign next year?

NAH, who you kidding. He'll probably run unopposed - like his last school board race!

Politicians who can get things done are unique in L.A., even if you do have to pay them off to make things happen. It's a BITCH when you support someone like Villaraigosa, hook, line ann stinker and he STILL can't pull nothing off. (Speaking of Mt. Washington, ask them about AV and his "I'll save the Southwest Museum" promise last year.) Then ask them what's on display in the museum THIS week (cobwebs, my child, just cobwebs).

I had high hopes for Huizar. The fact that he is trying to increase the salaries of the do-nothing LAUSD board members burns me up.

I'll take the corruption of Alatorre over this mental midget and political hack.

"He's getting slammed at community meetings"

Do you have proof of what you say?

Here is your proof.

OK

A) someone please delete the link above this post

b) isn't that "HEAD ON" commercial the most annoying thing in the universe?

5:28 We don't want to see pictures of your wife

Nasty

Did the New York Times place innocent lives in jeopardy by publishing the details of the secret SWIFT anti-terrorist-financing program?

One of our brave men in uniform, Lt. Tom Cotton submitted the following open letter to the New York Times which is now making the rounds on the Internet. As far as Cotton is concerned, the answer is "yes!"

Dear Messrs. Keller, Lichtblau & Risen:

Congratulations on disclosing our government's highly classified anti-terrorist-financing program (June 23). I apologize for not writing sooner. But I am a lieutenant in the United States Army and I spent the last four days patrolling one of the more dangerous areas in Iraq. (Alas, operational security and common sense prevent me from even revealing this unclassified location in a private medium like email.)

Unfortunately, as I supervised my soldiers late one night, I heard a booming explosion several miles away. I learned a few hours later that a powerful roadside bomb killed one soldier and severely injured another from my 130-man company. I deeply hope that we can find and kill or capture the terrorists responsible for that bomb. But, of course, these terrorists do not spring from the soil like Plato's guardians. No, they require financing to obtain mortars and artillery shells, priming explosives, wiring and circuitry, not to mention for training and payments to locals willing to emplace bombs in exchange for a few months' salary. As your story states, the program was legal, briefed to Congress, supported in the government and financial industry, and very successful.

Not anymore. You may think you have done a public service, but you have gravely endangered the lives of my soldiers and all other soldiers and innocent Iraqis here. Next time I hear that familiar explosion -- or next time I feel it -- I will wonder whether we could have stopped that bomb had you not instructed terrorists how to evade our financial surveillance.

And, by the way, having graduated from Harvard Law and practiced with a federal appellate judge and two Washington law firms before becoming an infantry officer, I am well-versed in the espionage laws relevant to this story and others -- laws you have plainly violated. I hope that my colleagues at the Department of Justice match the courage of my soldiers here and prosecute you and your newspaper to the fullest extent of the law. By the time we return home, maybe you will be in your rightful place: not at the Pulitzer announcements, but behind bars.

Very truly yours,

Tom Cotton

Baghdad, Iraq

When do we publish a secret?

Dean Baquet and Bill Keller The New York Times

Published: July 2, 2006

Since Sept. 11, 2001, American newspaper editors have faced excruciating choices in covering the government's efforts to protect the United States from terrorist agents. Each of us has, on a number of occasions, withheld information because we were convinced that publishing it could put lives at risk. On other occasions, each of us has decided to publish classified information over strong objections from the government.

Last month our newspapers disclosed a secret Bush administration program to monitor international banking transactions. We did so after appeals from senior administration officials to hold the story. Our reports - like earlier press disclosures of secret measures to combat terrorism - revived an emotional national debate, featuring angry calls of "treason" and proposals that journalists be jailed along with much genuine concern and confusion about the role of the press in times like these.

We are rivals. Our newspapers compete on a hundred fronts every day. We apply the principles of journalism individually as editors of independent newspapers. We agree, however, on some basics about the immense responsibility the American press has been given by the inventors of the United States.

Make no mistake, journalists have a large and personal stake in America's security. We live and work in cities that have been tragically marked as terrorist targets. Reporters and photographers from both our papers braved the collapsing towers to convey the horror to the world.

We have correspondents today alongside troops on the front lines in Iraq and Afghanistan. Others risk their lives in a quest to understand the terrorist threat; Daniel Pearl of The Wall Street Journal was murdered on such a mission. We, and the people who work for us, are not neutral in the struggle against terrorism.

But the virulent hatred espoused by terrorists, judging by their literature, is directed not just against our people and our buildings. It is also aimed at our values, at our freedoms and at our faith in the self-government of an informed electorate. If the freedom of the press makes some Americans uneasy, it is anathema to the ideologists of terror.

Thirty-five years ago, in the Supreme Court ruling that stopped the government from suppressing the secret Vietnam War history called the Pentagon Papers, Justice Hugo Black wrote: "The government's power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the government. The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of the government and inform the people."

As that sliver of judicial history reminds us, the conflict between the government's passion for secrecy and the press's drive to reveal is not of recent origin. This did not begin with the Bush administration, although the polarization of the electorate and the daunting challenge of terrorism have made the tension between press and government as clamorous as at any time since Justice Black wrote.

Our job, especially in times like these, is to bring our readers information that will enable them to judge how well their elected leaders are fighting on their behalf, and at what price.

In recent years our papers have brought to Americans a great deal of information the White House never intended for them to know - classified secrets about the questionable intelligence that led America to war in Iraq, about the abuse of prisoners in Iraq and Afghanistan, about the transfer of suspects to countries that are not squeamish about using torture, about eavesdropping without warrants.

As Robert Kaiser, associate editor of The Washington Post, asked recently in the pages of that newspaper: "You may have been shocked by these revelations, or not at all disturbed by them, but would you have preferred not to know them at all? If a war is being waged in America's name, shouldn't Americans understand how it is being waged?"

Government officials, understandably, want it both ways. They want us to protect their secrets, and they want us to trumpet their successes. A few days ago, Treasury Secretary John Snow said he was scandalized by our decision to report on the bank-monitoring program. But in September 2003, Snow invited a group of reporters from our papers, The Wall Street Journal and others to travel with him and his aides on a military aircraft for a six-day tour to show off the department's efforts to track terrorist financing. The secretary's team discussed many sensitive details of their monitoring efforts, hoping they would appear in print and demonstrate the administration's relentlessness against the terrorist threat.

How do we, as editors, reconcile the obligation to inform with the instinct to protect?

Sometimes the judgments are easy. Our reporters in Iraq and Afghanistan, for example, take great care not to divulge operational intelligence in their news reports, knowing that in this wired age it could be seen and used by insurgents.

Often the judgments are painfully hard. In those cases, we cool our competitive jets and begin an intensive deliberative process.

The process begins with reporting. Sensitive stories do not fall into our hands. They may begin with a tip from a source who has a grievance or a guilty conscience, but those tips are just the beginning of long, painstaking work. Reporters operate without security clearances, without subpoena powers, without spy technology. They work, rather, with sources who may be scared, who may know only part of the story, who may have their own agendas that need to be discovered and taken into account. We double-check and triple- check. We seek out sources with different points of view. We challenge our sources when contradictory information emerges.

Then we listen. No article on a classified program gets published until the responsible officials have been given a fair opportunity to comment. And if they want to argue that publication represents a danger to national security, we put things on hold and give them a respectful hearing. Often, we agree to participate in off-the-record conversations with officials, so they can make their case without fear of spilling more secrets onto our front pages.

Finally, we weigh the merits of publishing against the risks of publishing. There is no magic formula, no neat metric for either the public's interest or the dangers of publishing sensitive information. We make our best judgment.

When we come down in favor of publishing, of course, everyone hears about it. Few people are aware when we decide to hold an article. But each of us, in the past few years, has had the experience of withholding or delaying articles when the administration convinced us that the risk of publication outweighed the benefits. Probably the most discussed instance was The New York Times' decision to hold its article on telephone eavesdropping for more than a year, until editors felt that further reporting had whittled away the administration's case for secrecy.

But there are other examples. The New York Times has held articles that, if published, might have jeopardized efforts to protect vulnerable stockpiles of nuclear material, and articles about highly sensitive counterterrorism initiatives that are still in operation. In April, the Los Angeles Times withheld information about American espionage and surveillance activities in Afghanistan discovered on computer drives purchased by reporters in an Afghan bazaar.

It is not always a matter of publishing an article or killing it. Sometimes we deal with the security concerns by editing out gratuitous detail that lends little to public understanding but might be useful to the targets of surveillance. The Washington Post, at the administration's request, agreed not to name the specific countries that had secret Central Intelligence Agency prisons, deeming that information not essential for American readers. The New York Times, in its article on National Security Agency eavesdropping, left out some technical details.

Even the banking articles, which the president and vice president have condemned, did not dwell on the operational or technical aspects of the program, but on its sweep, the questions about its legal basis and the issues of oversight.

We understand that honorable people may disagree with any of these choices - to publish or not to publish. But making those decisions is the responsibility that falls to editors, a corollary to the great gift of our independence. It is not a responsibility we take lightly. And it is not one we can surrender to the government.

Dean Baquet is editor of the Los Angeles Times and Bill Keller is executive editor of The New York Times.

Since Sept. 11, 2001, American newspaper editors have faced excruciating choices in covering the government's efforts to protect the United States from terrorist agents. Each of us has, on a number of occasions, withheld information because we were convinced that publishing it could put lives at risk. On other occasions, each of us has decided to publish classified information over strong objections from the government.

Last month our newspapers disclosed a secret Bush administration program to monitor international banking transactions. We did so after appeals from senior administration officials to hold the story. Our reports - like earlier press disclosures of secret measures to combat terrorism - revived an emotional national debate, featuring angry calls of "treason" and proposals that journalists be jailed along with much genuine concern and confusion about the role of the press in times like these.

We are rivals. Our newspapers compete on a hundred fronts every day. We apply the principles of journalism individually as editors of independent newspapers. We agree, however, on some basics about the immense responsibility the American press has been given by the inventors of the United States.

Make no mistake, journalists have a large and personal stake in America's security. We live and work in cities that have been tragically marked as terrorist targets. Reporters and photographers from both our papers braved the collapsing towers to convey the horror to the world.

We have correspondents today alongside troops on the front lines in Iraq and Afghanistan. Others risk their lives in a quest to understand the terrorist threat; Daniel Pearl of The Wall Street Journal was murdered on such a mission. We, and the people who work for us, are not neutral in the struggle against terrorism.

But the virulent hatred espoused by terrorists, judging by their literature, is directed not just against our people and our buildings. It is also aimed at our values, at our freedoms and at our faith in the self-government of an informed electorate. If the freedom of the press makes some Americans uneasy, it is anathema to the ideologists of terror.

Thirty-five years ago, in the Supreme Court ruling that stopped the government from suppressing the secret Vietnam War history called the Pentagon Papers, Justice Hugo Black wrote: "The government's power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the government. The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of the government and inform the people."

As that sliver of judicial history reminds us, the conflict between the government's passion for secrecy and the press's drive to reveal is not of recent origin. This did not begin with the Bush administration, although the polarization of the electorate and the daunting challenge of terrorism have made the tension between press and government as clamorous as at any time since Justice Black wrote.

Our job, especially in times like these, is to bring our readers information that will enable them to judge how well their elected leaders are fighting on their behalf, and at what price.

In recent years our papers have brought to Americans a great deal of information the White House never intended for them to know - classified secrets about the questionable intelligence that led America to war in Iraq, about the abuse of prisoners in Iraq and Afghanistan, about the transfer of suspects to countries that are not squeamish about using torture, about eavesdropping without warrants.

As Robert Kaiser, associate editor of The Washington Post, asked recently in the pages of that newspaper: "You may have been shocked by these revelations, or not at all disturbed by them, but would you have preferred not to know them at all? If a war is being waged in America's name, shouldn't Americans understand how it is being waged?"

Government officials, understandably, want it both ways. They want us to protect their secrets, and they want us to trumpet their successes. A few days ago, Treasury Secretary John Snow said he was scandalized by our decision to report on the bank-monitoring program. But in September 2003, Snow invited a group of reporters from our papers, The Wall Street Journal and others to travel with him and his aides on a military aircraft for a six-day tour to show off the department's efforts to track terrorist financing. The secretary's team discussed many sensitive details of their monitoring efforts, hoping they would appear in print and demonstrate the administration's relentlessness against the terrorist threat.

How do we, as editors, reconcile the obligation to inform with the instinct to protect?

Sometimes the judgments are easy. Our reporters in Iraq and Afghanistan, for example, take great care not to divulge operational intelligence in their news reports, knowing that in this wired age it could be seen and used by insurgents.

Often the judgments are painfully hard. In those cases, we cool our competitive jets and begin an intensive deliberative process.

The process begins with reporting. Sensitive stories do not fall into our hands. They may begin with a tip from a source who has a grievance or a guilty conscience, but those tips are just the beginning of long, painstaking work. Reporters operate without security clearances, without subpoena powers, without spy technology. They work, rather, with sources who may be scared, who may know only part of the story, who may have their own agendas that need to be discovered and taken into account. We double-check and triple- check. We seek out sources with different points of view. We challenge our sources when contradictory information emerges.

Then we listen. No article on a classified program gets published until the responsible officials have been given a fair opportunity to comment. And if they want to argue that publication represents a danger to national security, we put things on hold and give them a respectful hearing. Often, we agree to participate in off-the-record conversations with officials, so they can make their case without fear of spilling more secrets onto our front pages.

Finally, we weigh the merits of publishing against the risks of publishing. There is no magic formula, no neat metric for either the public's interest or the dangers of publishing sensitive information. We make our best judgment.

When we come down in favor of publishing, of course, everyone hears about it. Few people are aware when we decide to hold an article. But each of us, in the past few years, has had the experience of withholding or delaying articles when the administration convinced us that the risk of publication outweighed the benefits. Probably the most discussed instance was The New York Times' decision to hold its article on telephone eavesdropping for more than a year, until editors felt that further reporting had whittled away the administration's case for secrecy.

But there are other examples. The New York Times has held articles that, if published, might have jeopardized efforts to protect vulnerable stockpiles of nuclear material, and articles about highly sensitive counterterrorism initiatives that are still in operation. In April, the Los Angeles Times withheld information about American espionage and surveillance activities in Afghanistan discovered on computer drives purchased by reporters in an Afghan bazaar.

It is not always a matter of publishing an article or killing it. Sometimes we deal with the security concerns by editing out gratuitous detail that lends little to public understanding but might be useful to the targets of surveillance. The Washington Post, at the administration's request, agreed not to name the specific countries that had secret Central Intelligence Agency prisons, deeming that information not essential for American readers. The New York Times, in its article on National Security Agency eavesdropping, left out some technical details.

Even the banking articles, which the president and vice president have condemned, did not dwell on the operational or technical aspects of the program, but on its sweep, the questions about its legal basis and the issues of oversight.

We understand that honorable people may disagree with any of these choices - to publish or not to publish. But making those decisions is the responsibility that falls to editors, a corollary to the great gift of our independence. It is not a responsibility we take lightly. And it is not one we can surrender to the government.

Dean Baquet is editor of the Los Angeles Times and Bill Keller is executive editor of The New York Times.

Traitors=Jail Time

Messrs. Keller, Lichtblau & Risen

TRAITORS

TRAITORS

TRAITORS

TRAITORS

Huizar is a wimp. He hasn't done anything for his district and people sneer when they see him. He's lost a lot of respect. His deputy Gustavo was heard telling people Huizar's motion for pay raise for school board members was Antonio's idea. Good going Gustavo laying out your boss. Gustavo is a mafisio corrupt idiot.

I support the actions of ADL LA and ALF. I have picketed side by side with Pamelyn Ferdin and Jerry Vlasak. If Vlasak says some humans have to die to save animals then so be it.

Why do I suspect the "Mayor Daniel" post is another example of fraudulent posting? What's that called -- "spoofing?"

Walter, you had ADL and ALF campaigning for you for Mayor, remember? You had no problem accepting help and donations from them. You worked hand in hand with their leader and members.

This is THE Mayor Daniel. I am proud to say that I picket and protest alongside great animal activists like Jerry Vlasak and Pamelyn Ferdin. Here is a photo of us protesting at Dave Diliberto's home.

http://photos1.blogger.com/blogger/2136/2608/320/015_12A.1.jpg

http://photos1.blogger.com/blogger/2136/2608/320/008_5A.jpg

I'm wearing jeans and a black sweat shirt holding a red sign. Pam is wearing brown pants and a reddish knit hat. Jerry Vlasak was also at the protest as an observer with a video camera. I am proud to say we are all very close friends.

Please, come visit my own blog at http://mayordaniel.blogspot.com/ where I show how incompetent Ed Boks the GM of Animal Services is.

11:33 PM,

If the editors are guilty of treason, then they will be prosecuted to the fullest extente of the law. If not, then this will blow away, and your bitter conservative butt will be left grinding its teeth.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home